Well, Ondine does just that by presenting a

fairy tale through a postmodern lens --

questions and all. The project started in

2007 when screenwriter-director Neil Jor-

dan was in Hollywood prepping for a stu-

dio film when the writers' strike derailed it.

With no sense of when the strike would

end, Jordan returned to his home in Ireland

to work on a script he'd been thinking

about for a long time. "I had that image of

a fisherman pulling a girl out of his net,"

Jordan recalls, "and I just wanted to see

where this would go. I knew I wanted to tell

a fairy tale without any special effects or

any elements of what you would tradition-

ally think of as magic."

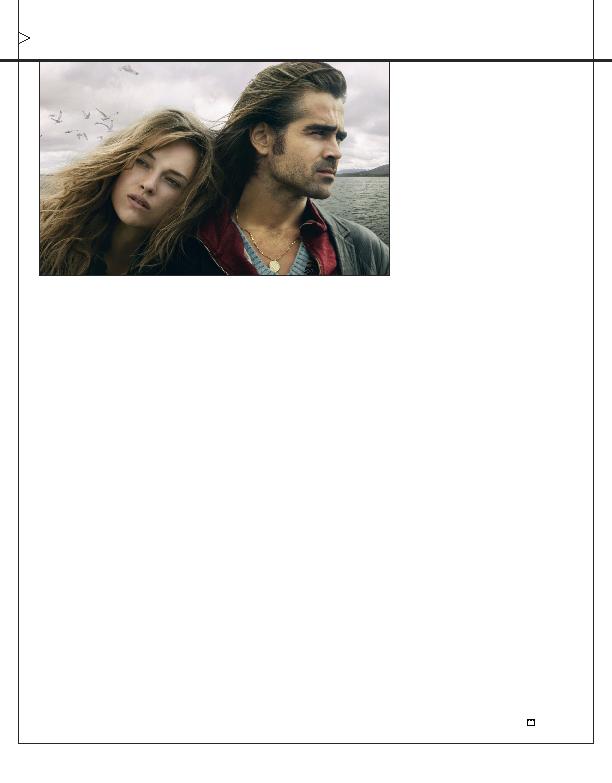

Ondine (Alicja Bachleda) out of one of his

nets. As the film progresses, it's debatable as

to whether or not she is a mermaid. Syracuse

takes her home, where magical things may

or may not start happening. He tells this

story to his daughter, Annie (Alison Barry),

who may or may not believe the fantastical

tale at hand.

you find in real life the archetypes found in

fairy tales? To his surprise, combining ele-

ments from real life and fairy tales turned out

wife, Maura (Dervla Kirwan), became a sort

of Evil Witch in the story, and Annie became

the curious child who serves as the skeptical

voice of the author. In fact, Jordan feels that

writing Annie helped the script really take

shape. "She was one of these kaleidoscopes

through which you can see things in a dif-

ferent light," he says. "It helps that the char-

acter is 10 years old, so [she] can easily

suspend disbelief when she needs to and still

be very realistic and wise when she needs to

as well."

believe in making page-count goals, how-

ever. "If a story is flowing it flows, and if it

doesn't flow then it doesn't flow," Jordan

says. "There seems to be very little I can do

about it. Sometimes, characters are just very

unwilling to come alive and speak to you. If

the character is alive, suddenly the dialogue

flows and your instincts just know what

should happen next. If I'm forcing it, it's gen-

erally a bad thing. I generally have to wait

and let the story speak to me."

grounded in reality. He explains, "I wanted a

realistic portrait of a small fishing town [to

explore] people living their lives the way

they do nowadays. They're divorced, they

have problems with their children, they have

and some are not."

win custody of Annie. But, as we know, drama

is critical and our hero must choose between

succumbing to his past, represented by Maura,

or embracing what his future could hold, rep-

resented by Ondine and the town priest.

"When I started writing this, I didn't know the

character of the priest would be there," Jordan

says. "I just thought it would be fun to have

Syracuse in a town where they don't even have

that language for AA and 12 steps, so he forces

the priest to be his AA buddy in the confes-

sional. But then Maura wants to bring him

back into his old life, so she does that old Irish

thing of giving him a drink. And once she's

done that, she knows she's got him back into

that mess he's been in forever."

dramatic question that Jordan felt would

make or break his script. "I'm writing this

fairy tale that turns out to have all of its basis

in reality," he says. "The whole thing turns

out to have a realistic explanation. But then

I wondered, if you tell a fairy tale successfully

enough, and then you reveal to the audience

that it wasn't a fairy tale, will they be angry?

Will they feel cheated? Will they feel manip-

ulated in some way?" As with the fisherman

pulling a girl from the sea, Jordan points to

another image to answer this question. Late

in the film, Ondine is sitting on a rock with

the sun beating down on her. We see her

shadow on another rock, on which she

seems to have a tail -- until it's revealed to be

a piece of driftwood. "If she hadn't moved

her legs it would've kept looking like a tail,

but she moves her legs and it's a piece of

driftwood," Jordan says. "It was that kind of

movie. It's a particularly Irish story."

how, when and even if people choose to ex-

amine their own lives and the lives of oth-

ers through a fantasy filtered point of view.

"It all comes down to how certain events

are viewed," Jordan says, "When Syracuse

pulls her out, if she doesn't come alive it's

a horror story, and if she does then it's a

fairy tale -- simple as that, really. I just had

that basic image and as a writer you have to

ask what this image is trying to tell you and

where does it want to go. That's what the

script was about in the end."