crying. And in these moments, no one's

thinking, `This is a cartoon.' No. These char-

acters are alive, they're real." Recently, the

chatter has been about Oscar-winner Up's

opening "Married Life" montage. Ultimately,

it's all about caring. As Frank Capra once said,

"The whole thing is, you've got to make them

care about somebody."

pening, but whom it is happening to. We go

to movies to see characters solve problems

and handle relationships. But what is often

forgotten is that without an emotional con-

nection to these characters, there can be no

caring about the journey these characters take.

This leads to an unsatisfying experience,

which means the movie ultimately fails.

requirement for any good

screenplay. But Pixar's sto-

rytellers do it masterfully,

which is the greatest factor

in their films' success. And

this is in spite of the extra

challenge of making us con-

nect emotionally with non-

human characters such as

toys, bugs, monsters, cars,

fish, rats and robots.

In my book, "Writing for

Emotional Impact," I pres-

ent the three areas writers

should focus on to make

pathos, humanity and admiration. Specifically,

we care about characters we feel sorry for, like

when a character is unjustly abused, aban-

doned or betrayed. We also care about char-

acters who have humanistic traits, like when

they're being nice to another human being

or animal, or when they care about a cause

or anything other than themselves. Finally,

we care about characters who have admirable

qualities. For instance, we admire characters

who are good at what they do, who are pow-

erful, attractive, charming, funny or wise.

their goals, needs and the ultimate journey

that makes up the film's plot, writers should

make us care about the characters from the

very start, preferably within the first few min-

utes of their introduction. Reading a script or

watching a film is like a dance of emotions,

anticipation, curiosity, amusement, ten-

sion and surprise. When it comes to

characters, the dance is along an empa-

thy line (I care, I like) and an enmity one

(I don't care, I dislike). This happens fast.

The moment characters are introduced,

we start building opinions about them.

Everything they say and do counts. This

is why we should create that emotional

connection as soon as possible.

for instance, Woody is upset about being

replaced by a new toy and losing Andy's

love -- a simple, honest emotional core,

and something everyone can relate to. In

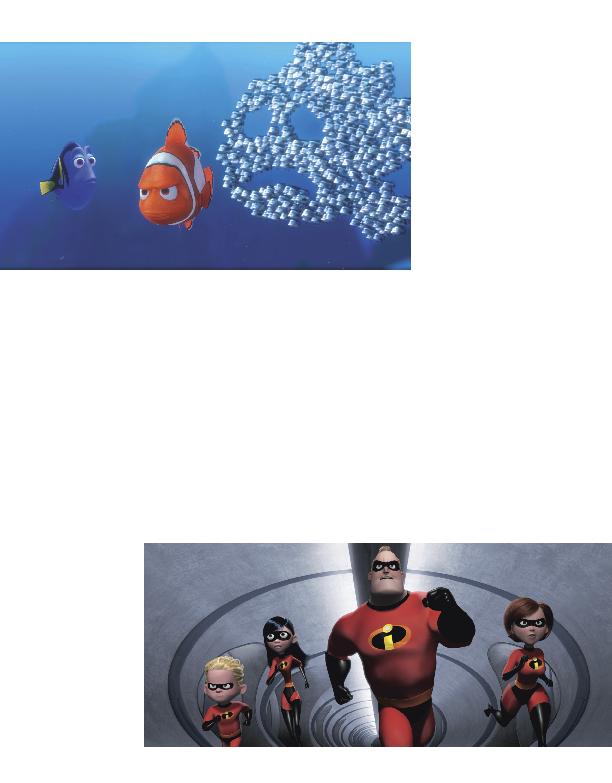

Finding Nemo, a father and son are sepa-

rated. The same thing happens in Rata-

touille, as Remy is separated from his

characters are alone and we feel sorry for

them. This is Pixar's strength: Its films offer a

genuine emotional component that runs

deeper than traditional animated features.

They make sure to have a complete emotional

connection before anything else, and this is

in spite of the extra challenge of making us

connect emotionally with non-human char-

acters. Even when the film is making us care

for a cute clown fish or a family of super-

heroes, the emphasis right off the bat is to cre-

ate a moment that makes us feel sorry for the

character. In Finding Nemo, for instance, we

begin with a dark, traumatic sequence in-

volving an expectant father who loses all but

one of his 400 babies to a hungry barracuda,

which is followed by seeing his only surviv-

ing son get kidnapped by a scuba diver. And in

The Incredibles, right after the interview mon-

tage that introduces the superheroes -- and