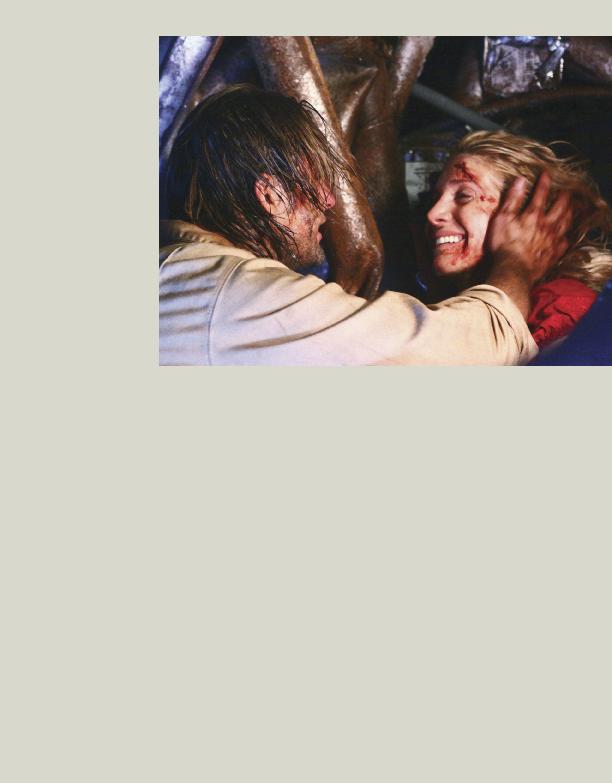

O'Quinn) is, in fact, the

smoke monster who has been

heard and glimpsed many

times since the pilot but until

this point had never been per-

sonified as a character. The

monster has become a major

character in the final season

with the confirmation that it's

not only intelligent, but it's

also the man in black (Titus

Welliver) seen in season five's

finale, "The Incident," and in

this season's "Ab Aeterno."

"The approach to a lot of

these mysteries from the

start," Horowitz says, "has

been [that] people are more

interesting than objects or

facts. I think making some-

thing a person allows you to

then make it a character,

which then allows you to

make it something the audi-

ence can get invested in." He

and Kitsis confirm this decep-

tion by the false Locke has

been the plan since the mur-

dered man first reappeared alive on the is-

land in season five's "The Life and Death of

Jeremy Bentham."

peared more as the show progressed: the

stone lighthouse, with its elaborate gears and

mirrors; the hidden passages of the Temple;

and, of course, the infamous glowing don-

key wheel that moves the island through

space and time. "We spend a large amount

of time involving the technical aspects as

well as the story aspects," Horowitz says.

"And Carlton, God bless him, is one hell of

a sketch artist." It's not uncommon for ex-

tensive diagrams to be drawn on the white-

boards with hours spent discussing the actual

mechanics behind story elements.

land or its mysterious master, Jacob (Mark

Pellegrino), need a gear-driven, mathemati-

cally precise lighthouse when the end result

is magic? "I think because it's too easy," Kit-

sis muses. He points out the show works best

when things are left in the gray areas of "is it

or isn't it?" and mysteries that could have

scientific or supernatural answers are posed.

hate the magic, and there are people who

love [the magic]," he says. "For us, we don't

want to come down either way. There's defi-

nitely some magic in the show but there's

definitely some science. That's a huge theme

in the show -- man of science versus man of

faith. Things like a donkey wheel that needs

to be turned illustrate that."

the time travel, which dominated season

five. While fans tirelessly debate the finer el-

ements of time travel -- both online and

over a beer -- it should be noted that the

show's producers debate it as well. The show

first toyed with time travel in the fourth sea-

son episode "The Constant," where a funda-

mental rule for the show was formed. "We

don't do paradoxical storytelling," Lindelof

says. "We're more interested in the story-

telling where you travel to a future and

there's nothing you can do to stop it from hap-

pening. In fact, the more you try to avert it

from happening, the more you might po-

tentially be the cause of that disaster." Cuse

adds that it's difficult to have stakes if the fu-

ture is always alterable, because there are no

real consequences. Horowitz points out that

it's illogical to make something happen in

Kitsis, however, is a firm believer in, "Back to

the Future time travel," and claims an unal-

terable history means a dull time travel story.

"You hear those arguments on the show be-

cause those are arguments in the room," he

says with a chuckle.

right from the start, allowing people to get

drawn in instead by the characters and the

drama of the plane crash. "There's obviously

this loud, menacing monster out in the jun-

gle," he says, "but you never see it. So for

those people who don't want to be watching

a science fiction show, like a Rorschach test,

they project. Whatever it is that threw the

pilot up into that tree, there's got to be a ra-

tional explanation. Even when they saw

`Walkabout,' they say, `I don't know how

Locke ended up in the wheelchair, so maybe

it was psychosomatic and the plane crash

jarred his memory free.'" He mentions shows

such as Heroes or the short-lived LOST-coat-

tails show, Invasion, which both opened with

sci-fi events rather than letting people slowly

come to their own conclusions while they

became invested in the characters. "If you

watch the pilot for Heroes and Nathan Pe-

trelli flies up into the sky and catches Peter