nal language of their source material. Not so

with director Denis Villeneuve's Incendies, an

image-driven adaptation of an incredibly

dense, dialogue-heavy play by celebrated

Lebanese-Canadian writer Wajdi Mouawad.

the original show. His film -- which earned

rave reviews at the Venice, Telluride and

Toronto film festivals and has since been sub-

mitted as Canada's official Oscar foreign lan-

guage entry -- is the exact opposite. In place

of a series of long, one- and two-page mono-

logues, the words are sparse and minimal;

meanwhile, on-screen, the near-empty space

of the stage opens up to a sequence of ar-

resting, unforgettable images.

theater in Montreal, "but I was just totally as-

tonished by the story and how powerful it

was." Moved by the play, Villeneuve met

Mouawad for coffee the following day and

proposed making "Incendies" (aka

"Scorched") into a film, but the playwright

was skeptical, having personally directed a

film version of "Littoral," the first installment

in his politically charged trilogy.

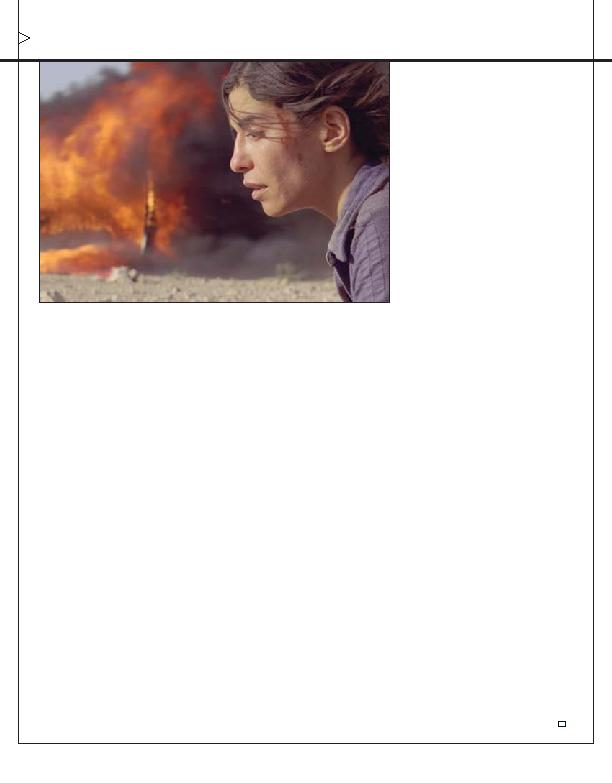

the horrors of Lebanese history -- Incendies

tells the story of Nawal, a Middle Eastern

woman whose peculiar will triggers an inves-

tigation into her past. According to her final

wishes, Nawal asks to be buried in an un-

marked grave until her grown daughter and

son are able to erase her shame by each deliv-

ering a letter to their father and brother.

Mouawad spelled out the obstacles ahead: In-

cendies was too big to put on screen, the play-

wright explained and, besides, it was set in an

imaginary land (based on Lebanon, but re-

imagined for artistic effect), which would be

difficult to translate to film.

suggested by the play and sent them to

Mouawad. "It was a total brainstorm," Vil-

leneuve remembers. "I pitched him an orgy of

images inspired by different scenes and ideas

from the play, like the opening scene where

the kids are being shaved by military men --

that's not in the play, but he loved it."

as he understood that it would be a lonely and

difficult journey. According to Villeneuve,

Mouawad told him, "I suffered a lot writing

`Incendies,' and you're going to suffer, too."

for Paris to work on his next play.

Canadian with no personal ties to the Middle

East. "I had been saying to myself, `When I

get the rights, it will take me three months,'

but the truth is it took me six months before

I put one word to paper," says Villeneuve,

who used research and meditation to find

the right angle.

entry point. Villeneuve kept four key char-

acters and started rebuilding the story

around that idea. "I had to modify it a lot in

order that it became cinema," says the direc-

tor, who claims he hates flashbacks in films.

"What I liked about the structure of the play

is how it captures the feeling of two present

times." Where another director might have

chosen separate looks for these sequences,

Villeneuve invited a measure of confusion as

the story moves back and forth. "It's written

like this in the screenplay, as a game of space

and time," he says. "It's like there are ghosts

or echoes, which creates a kind of dialogue

between the characters."

According to Villeneuve, his goal was to

make a totally silent movie, though it was ul-

timately easier for the characters to describe

things he couldn't afford to show because of

budget constraints.

acters in the movie are 10,000 times more

contained," says Villeneuve, who found that

by taking a line here and there from

Mouawad's "beautiful poems," then trans-

lating the rest into images, he could elicit the

emotional response he wanted -- almost like

a form of visual haiku.

with the images you are putting on the

screen," Villeneuve says. Rather than staging

the most violent scenes (described in graphic

detail in the play), the director decided to

show just enough to suggest their horror, pre-

ferring to feature silent, introspective mo-

ments in which the characters digest what

they've experienced (such as the bus massacre

Nawal narrowly survives) -- a strategy ac-

counted for in advance at the screenplay level.

"Cinema for me is about images. It's always

beautiful when it can be done without dia-

logue," he says. "It's a link with poetry."