run off together, jumping into the lake and

breaking the spell at the tragic expense of

their lives.

still had to go down a lot of wrong roads be-

fore getting to the final script." Without

Heinz's murder mystery angle, Heyman had

to figure out what would serve as the plot en-

gine to drive the story forward. "It's very hard

when you're talking about training for a

role," he says. "That's not a particularly dra-

matic or universal thing for the audience."

So Heyman experimented with various ideas

that might make the story more compelling.

In one early version of his script, Nina was

dent star (a character played by Winona

Ryder in the film), until Nina did something

incredibly back-stabbing to get the role.

"That was a wrong path," Heyman says.

director-choreographer was a stand-in for her

prince (played by French actor Vincent Cas-

sel and modeled after George Balanchine,

who famously married and divorced his

muses over the years), Heyman still had to

figure out who the sources of conflict would

be. "The unifying arc was going to be how

someone who's a White Swan transforms

into a Black Swan, personality-wise, charac-

ter-wise -- what that means, in terms of

being darker, seductive, free, as opposed to

rigid and controlled," Heyman explains.

the supernatural, scary aspect," says Hey-

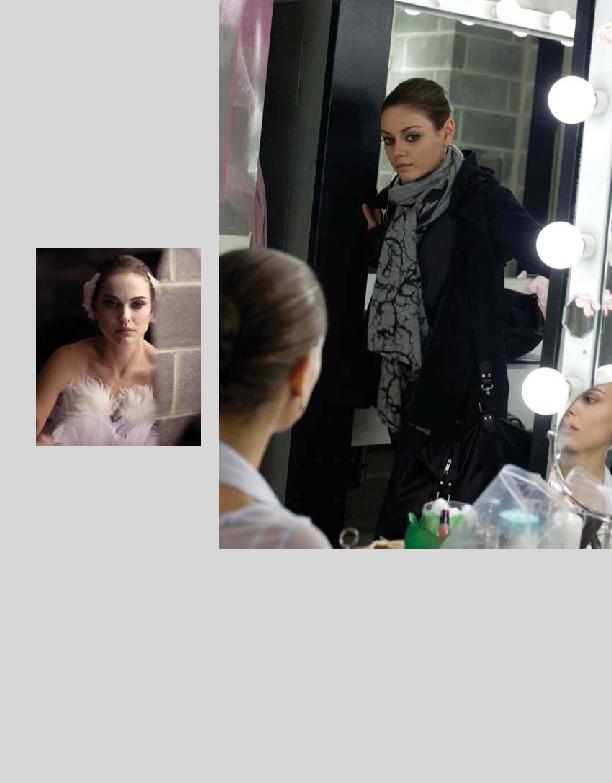

man, who came up with the idea that Lily

would be a different dancer (played by Mila

ties that Nina needed in order to properly

play both roles in the ballet. "That's where

the tension started to come from, so that was

one of the elements we settled on early," he

says. But something was still missing.

mother (Barbara Hershey). "If this is about a

White Swan who becomes a Black Swan, the

mother becomes the real thing standing in

the way," he says. "Nina really needed to es-

cape her mother to achieve what she

wanted, and that relationship is what helped

pull us through and gave us the real-world

the mode of Polanski's Repulsion, which

had appealed to both Heinz and Aronofsky

from the start -- the character is effectively

her own antagonist as well. "We worked

very hard to make sure that all of the sur-

rounding characters of the film were actu-

ally real antagonists, too," Heyman says.

"It's hard to pull off something where it re-

ally is just all in her head. It's hard to sym-

pathize with a character like that." So it

became a challenge to figure out how

everyone could be seen as either a positive