the loss of a child, but that doesn't mean it's a

comedy. "I don't think there's a joke in the

script," says playwright David Lindsay-Abaire,

who adapted his own Tony-nominated drama

for the screen. "I was trying to create characters

who were human. Whenever something horri-

ble happens, at least in my family, there's a very

dark streak of humor that makes its way into the

situation. More often than not, it's a coping

mechanism, but it's also because we are funny

people, so humor often comes at inappropriate

times and in inappropriate ways," he explains.

The play earned Lindsay-Abaire a Pulitzer.

to sell the movie rights for Rabbit Hole to Blos-

som Films, Nicole Kidman's production com-

pany. As he advises theater directors in the

original author's note of his published script,

"It's a sad play. Don't make it any sadder than

it needs to be." Laughter, he understood,

would get audiences through what might oth-

erwise feel like melodrama, and it would also

set apart material that had already been cov-

ered quite seriously in such films as Ordinary

People and In the Bedroom.

on-screen was to do the adaptation himself --

play; I didn't need a bad film version," he says.

And though it may sound like the writer was

angling for control, he was simply trying to

avoid the disappointment that had accompa-

nied his previous Hollywood experiences.

"Everything else I've ever worked on has been

miserable," sighs Lindsay-Abaire, whose previ-

ous screen credits include Robots ("A very sweet,

cute animated movie that wasn't the movie I

signed on to write") and Inkheart ("There's more

of my work in there, but that movie got so

chopped up and rewritten, and had a prologue

and epilogue tacked on," he says).

might have, since he wasn't shy about over-

hauling aspects of his own play. "I had lived

with these characters for five years. I knew

them so well, I didn't have to worry about

how they would respond in a new situation,"

he explains.

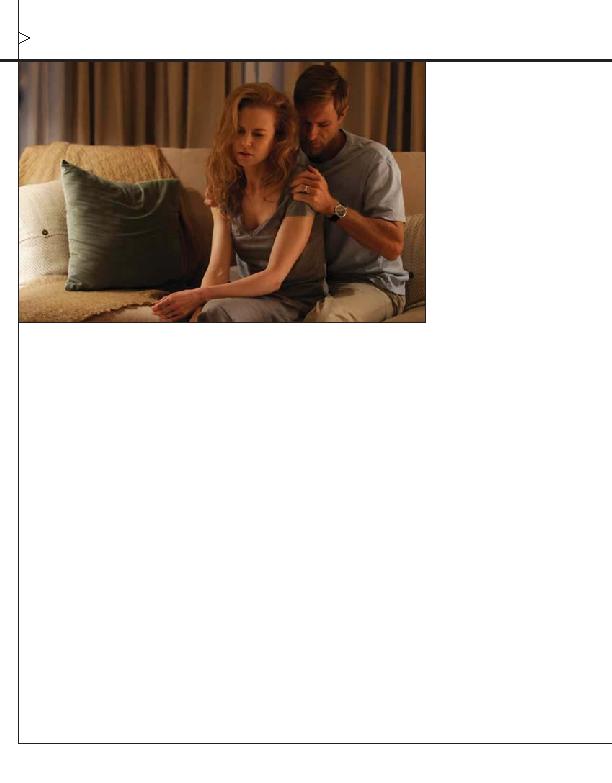

quently discuss grief counseling ses-

sions and their feelings about Jason

(Miles Teller), the teenage driver who

accidentally killed their son with his

car. Thus, the first idea added by Lind-

say-Abaire in the film was to present

these moments as proper cinematic

scenes. "One of the things the play had

going for it is that it had a fairly in-

volved off-stage life," Lindsay-Abaire

says. "For example, the support group

is talked about a lot in the play,

Howie's potential affair is hinted at,

and then there are things like the su-

permarket scene, where Becca has an

encounter with a woman and her

young son. In a film, we can go to that

support group and meet those people.

And even though I hadn't written

those scenes directly, I had already

written them in my head."

five actors unfolded to include other

characters and a whole world beyond

the domestic prison Becca and Howie

had created for themselves (on stage,

the same house they'd made to raise

sence, to the point that they end up deciding

to sell it). Howie also became a stronger char-

acter, with the idea that he responds to Becca's

emotional detachment by seeking attention

from another woman developing into a

proper subplot -- something that had inspired

performers to write Lindsay-Abaire in the past,

demanding to know whether Howie actually

cheats. "In the play, it's really up to the actor

to decide how he's going to play those scenes,"

he says. "If you really want to know what I

think, watch the movie."

group meetings with another grieving parent

named Gaby (Sandra Oh). These scenes con-

trast nicely with what Becca is going through

at the same time -- secretly meeting with Jason,

the young man who struck down her son. In

the play, it's Jason who reaches out to the griev-

ing family by writing a letter in which he asks

to meet them, though Lindsay-Abaire moved

that subplot out of the house. Now, Becca spots

Jason by chance and becomes the one to initi-

ate contact. "That was me putting on my

screenwriter's cap, trying to activate Nicole's

character more," Lindsay-Abaire explains.